Component Language Interface

Dec 15, 2025

In this post, I'd like to first motivate the use of boundaries in the systems we build, and then propose some ideas about how to implement the interface between these components that we have bounded.

The Economic Value of Information

A number of years ago, I gave a talk titled, Stop making mud pies!. The idea that I wanted to convey is that the systems we build need to be resilient to contradictory information, but that we also want to use new information as soon as possible because it helps us select between the better of two options.

At the time, there was a lot of confusion and outright FUD about microservices, so I wrote a couple posts about my ideas: The entire universe of microservices in 17.5 minutes or less and My theory slays your devil in the details.

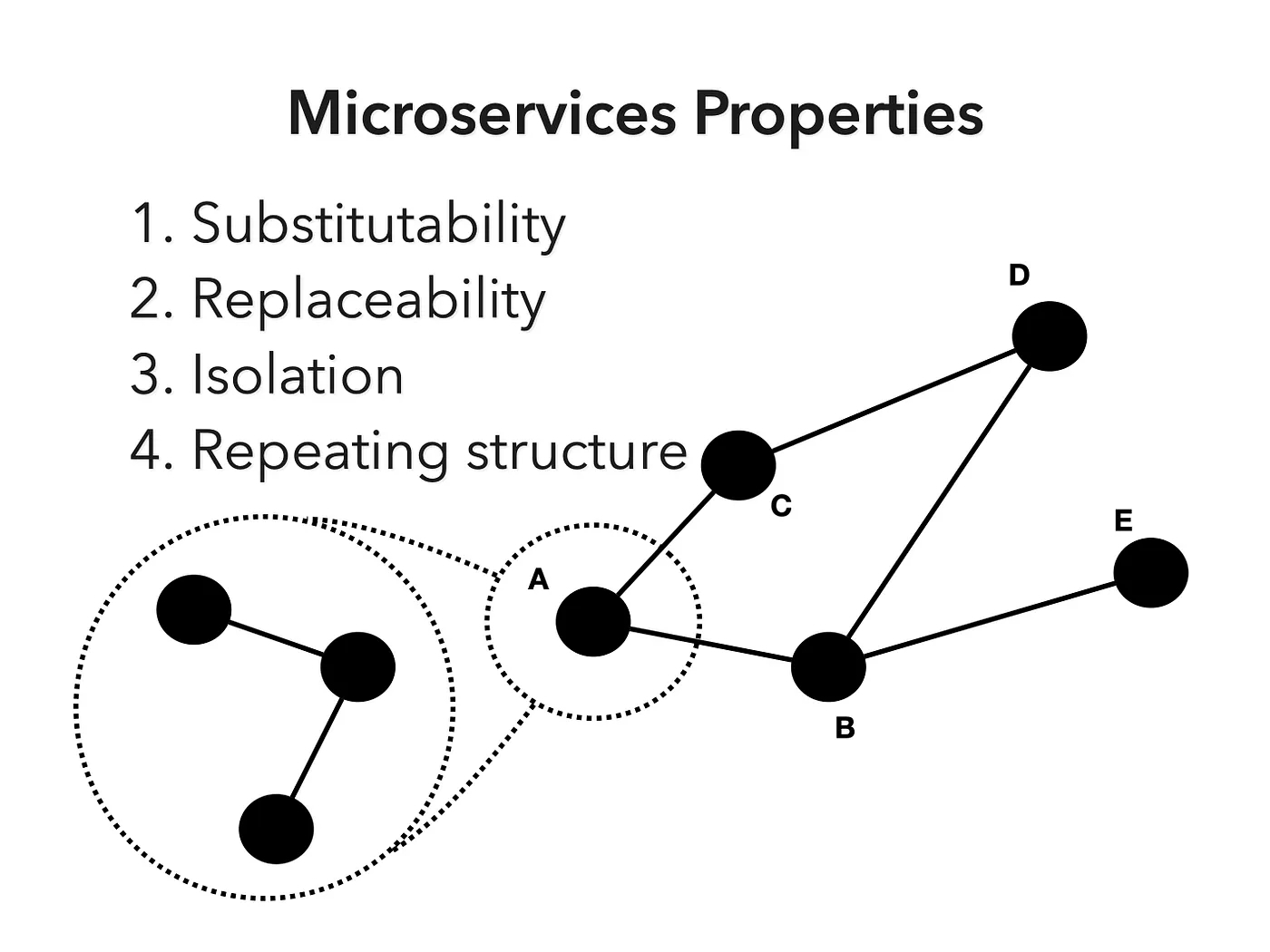

So in the image below, don't get distracted by the mention of microservices and instead think about any component of a distributed computation.

Well-bounded Systems

The idea in this graphic is that with these four properties, you can build a system that can utilize new information as quickly as possible and at lowest cost, provided that you can make the boundaries around components as small as necessary.

Why is that? Creating, operating, maintaining, and changing or updating code requires work, and work requires energy, and in this universe, energy has a cost.

The bigger the component, the more likely new information will contradict some existing information used to create that component or that the component uses in its operation.

Generally, having contradictory information compete doesn't work very well in a system. So we want to limit the impact of the existing information and begin utilizing the new information as soon as possible in such a way that we derive value from it.

The value of a "component" is two-fold:

- It provides a boundary that contains (and separates) what's inside it from what is outside it; and

- It also provides a "contact surface" or "interface" between the component and other things that interact with it.

Back then (i.e. more than ten years ago), most of the conversations around microservices focused on how quickly components could be added or changed, and how this enabled teams to work more quickly because there was less overhead to the integration activities, the system was less likely to break from a change, etc.

These are all perfectly valid, but the reason they're important is the economic one I've just explained.

But the flip side of finer-grained components is that the operations supporting these components become a bigger and bigger proportion of the total cost of the component. Of course, it's possible to reduce the overhead, and systems like Kubernetes, Istio, and others were created for this purpose.

However, given existing approaches to infrastructure, the "minimum" component size that is usable remains very large compared to what it could be. If you don't believe that, talk to someone who has been forced to confront AWS Lambdas recently (particularly when AWS is building its own infrastructure with them and that bleeds into other services you want to use).

So, let's take a closer look at components and their interfaces.

Defining Component Interfaces

These examples are toys, no question about that. But they are useful in that they faithfully illustrate some of the issues of the machinery we have available at the interface between components.

In the first example, we have two operations. One operation depends on the computation performed by the other:

def greet(name)

return "Hello, #{name}"

end

def say_hello

greet "World"

end

puts say_helloAnd, of course, if we run this code we should expect to see the following:

irb(main):009:0> puts say_hello

Hello, World

=> nilNow, let's assume that the greet operation is in another service on a different machine. The typical way (with a few abstractions here) would be to interact with it something like this:

require "json"

def greet

json = File.read "greet.request"

data = JSON.parse(json, symbolize_names: true)

resp = "Hello, #{data[:name]}"

File.write "greet.response", resp

end

def say_hello

data = { name: "World" }

json = JSON.generate(data)

File.write "greet.request", json

greet

File.read "greet.response"

end

puts say_helloRunning this code, we see basically the same thing:

irb(main):018:0> puts say_hello

Hello, World

=> nilAnd just to double check that the interchanged data really was written:

$ cat greet.request

{"name":"World"}%

$ cat greet.response

Hello, World%Of course, I hand-waved over a few important details. The actual data transmitted could have been gzipped, of course, and there's also a bunch of network machinery in there, operating system kernel shenanigans, etc.

Let's take a step back for a moment. This obviously works. Nearly every application in use today across the world that talks to a computation resource on a different physical machine does something like this.

But why?

It's not a superficial or purely rhetorical question. Yes, one simplistic answer is that it works. A bunch of nuanced answers involve this or that thing about separation of concerns and inter-operability. These are important, too.

But there are other ways to do this. Here's one:

def greet(name_provider)

return "Hello, #{eval name_provider}"

end

def say_hello

data = { name: "World" }

greet "#{data.inspect}[:name]"

end

puts say_helloYes, that worked:

irb(main):010:0> puts say_hello

Hello, World

=> nilHere's another one:

def greet(name_provider)

return '"Hello, %%s" %% "%s"' % eval(name_provider)

end

def say_hello

data = { name: "World" }

op = greet "#{data.inspect}[:name]"

eval op

end

puts say_helloI know by now you're just going to believe me when I say this code produces the same result:

irb(main):011:0> puts say_hello

Hello, World

=> nilBut what is different about these last two examples, and this last one in particular?

I was hoping to show off some of the cool Rubinius features in this post to illustrate what might be possible with a language interface, but other matters intervened, so I'll have to write a follow-up post.

But for now, you can inspect the usage of eval in these examples as a stand-in for a full language tool chain accessible from and usable by source code.

What this highly artificial example intends to illustrate is that it is perfectly possible to use language (i.e. executable code) as the interface between components.

These ideas are not new. Elsewhere I've written about this, but if curiosity has gotten the better of you, you can immediately go read about Actors: A Model of Concurrent Computation in Distributed Systems, look at Erlang, check out Concepts, Techniques, and Models of Computer Programming, or play with Unison.

The last example highlights something else that is really important for the next generation of applications and computational infrastructure that we must build: it's essentially "peer-to-peer".

There is no requirement whatsoever that networked, distributed applications must be "client-server", and in fact, the prevalence of this style of application does little more than ensure the unfortunate, inefficient, and often dangerous consolidation of power by companies like Meta and Google. The internet is inherently a peer-to-peer system and the wrong-turn into predominately client-server architectures is one that can be corrected at any time and with great advantage.

In these examples, there's no reason that greet and say_hello must live on the same machine or within the same operating system process, but equally, there's no reason they must exist on separate physical or virtual machines either. In fact, in the process of computation, they may be either or both.

One other thing to mention, the "language interface" becomes many times more interesting when we consider the possibility that the "interface" between these two components is not statically defined, but that it could be the result of a computation, and in fact, one generated by a machine intelligence.

Now again, don't mistake what I'm illustrating here. I'm not saying use Ruby eval as the interface. I'm saying, use the rich possibilities of languages proper as the interface. This will both be more powerful, and if properly constructed, more robust and resilient that the existing "APIs" between systems.

It is true that we don't yet have the infrastructure to make these scenarios transparent and efficient, but it's also true that what's necessary to make this possible is quite well understood and within our reach.

But even if you've followed along to here and think these may be good ideas, it's still perfectly reasonable to wonder whether up-ending the current paradigm is necessary. To answer that, I'll point back to what I opened this post with, namely that the ability to deploy new information to make decisions between the likely better of two options as efficiently as possible should be our guiding light.

If there's a way to do that that does not require building Component Language Interfaces, then so be it. After all, this is both definable and measurable, you don't need to take my opinion for it, and I'd never ask you to.

Stay tuned.