The weekly Vivarium for Week 4

Saving an Afternoon in the Library

There is a quote I shared in last week's newsletter that I just cannot get out of my head. You may recall it from the Markus on AI post about LLMs, A trillion dollars is a terrible thing to waste:

An old saying about such follies is that “six months in the lab can you save you an afternoon in the library”; here we may have wasted a trillion dollars and several years to rediscover what cognitive science already knew.

There's another quote that should always be walking hand-in-hand with this one by the legendary Richard P Feynman:

The first principle is that you must not fool yourself — and you are the easiest person to fool.

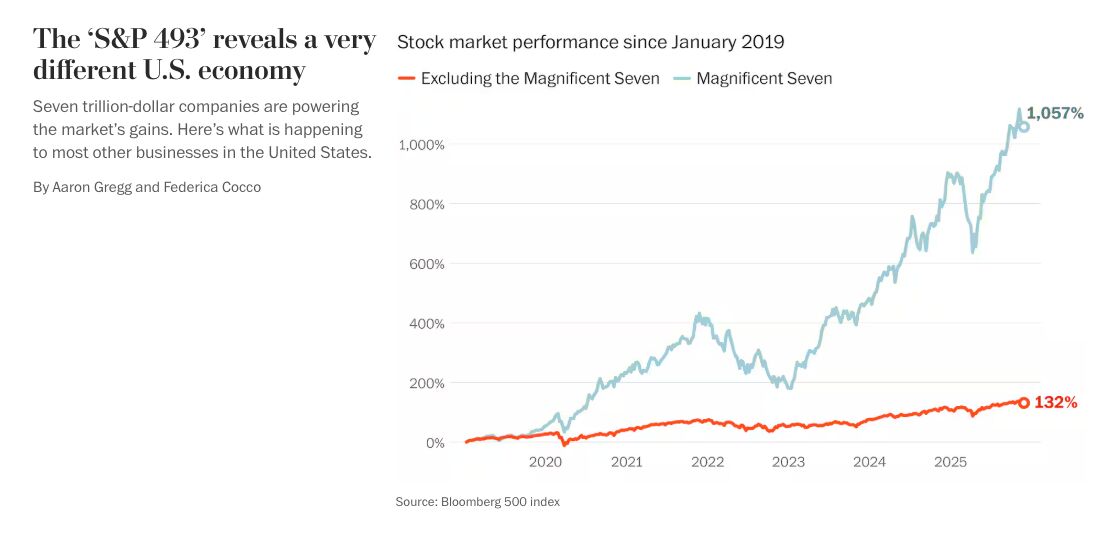

Look at this beauty from a post by Brian Krebs last week. It's comparing the performance of the "AI Bubble Companies" (apparently known as the "Magnificent Seven" in honor of their likely supernovae-like impact to the world economy) versus all the other mediocre companies in the much-touted S&P 500.

If LLMs were a broadly transformative technology in the way that they have been proclaimed (Altman's "a PhD in your pocket", etc.), we would see that vividly in the economic data.

There is no way to mistake this simple and fundamental fact given that graph. This is not "early days", there's no legitimate way to argue that businesses are still getting their feet under them, etc. The tech has been around for a few years now, it requires no real skills to type things into a chat window, and yet...

This week, I want to use this graph as a lens to relate three things:

- I attended two local AI events last week. One of the events was a regular meetup, and the other was a panel discussion about the impact of AGI on society;

- I have been using LLMs (mostly ChatGPT, but also Claude and Gemini) extensively for almost two years and I have a consistent set of, unfortunately unpleasant, experiences; and

- I'm graphing the allocation of my time for the last quarter and considering the likely best way to spend it for the remainder of this month with respect to projected ROI.

Local AI Events

Portland is not a big city and certainly doesn't stand out on any "tech wow" metrics (I think that's a thing, right?), but we do think of ourselves as the "Silicon Forest" and we've got amazing coffee, good food, a lot of rain, and some other things we can discuss in person sometime.

I was curious to see what a local AI meetup might look like, who would attend, etc. A few weeks back, I attended another (fancy, catered) event sponsored by IBM, but that was literally the first "AI-focused" event I've ever been to in any city.

For both events this week, I was only an observer, not a participant, so these are my recollections and opinions, where the usual caveats apply.

The panel discussion event lasted three hours and appeared to hold the attention of the audience. There were several questions from audience members, and it seemed like people were generally satisfied with their experiences.

The panel participants were (to the best of my recollection):

- Professor R, an economist;

- Professor S, a law professor at a prestigious private college;

- Professor T, a professor of government studies at a public university;

- Professor U, a professor of medical ethics at a renowned medical university.

The moderator Q is a person who claims to have invented an approach to AGI ("artificial general intelligence") around ten years ago, but offered no demonstration of that except for some static screenshots and a couple anecdotes (in his presentation at the first event, not the panel discussion).

I'll make a few points, and then elaborate on some thoughts:

- Because I was intentionally an observer of both groups (the speakers and the audience), I did not ask questions or interject at any point during the panel;

- I had never met the panelists before, but I have known the moderator for around ten years;

- None of the panelists displayed a knowledge of AI or LLMs beyond some simplistic summaries, like "they are stochastic parrots" and "they don't think";

- Despite asserting that he has created AGI, the moderator also claims that no one has a "scientific definition" of intelligence;

- The topics for the panel explicitly excluded a discussion of AI other than the framing premise, "Assume that 'AGI' exists", but "AGI" remains undefined.

Generally, I can see some value in a discussion under this premise with this group of experts. Here's the thing, though: If we're going to extrapolate from a premise, but the premise has very little to support it, what is the value of that activity?

Suppose I say, "Assume that faster than light travel is not only possible, but quite inexpensive and requires nothing more than some copper and aluminum in a certain configuration. Where will civilization be in ten years?" Even if we accurately extrapolated from that premise, of what utility would the results be?

Returning to the panel event, the possible cases would appear to be: AGI will be one of:

- Incredibly, possibly "infinitely", more powerful than human cognition;

- About the same as human cognition; or

- Not as powerful as human cognition.

We have instances of item #3 already, they are factory automation robots and we can speak intelligently about their impact on society.

We have a reasonable proxy for item #2 in the several decades of off-shoring "knowledge work" to areas with significantly lower standards of living (i.e. much cheaper to employ for owners of capital).

We have absolutely no idea of item #1 because, as David Deutsch points out in The Unknowable & How To Prepare For It, we cannot predict the impact of new knowledge because it brings with it new problems. I highly recommend watching that video, as well as A New Way To Explain Explanation.

Since the panelists are not experts in AI, it's probably not fair to expect them to research AI before participating, but given the huge claims made for LLMs, it should not take much time to get a thorough crash course and be able to speak with more nuance than, "I don't believe machines will ever think."

At the same time, no one in the audience raised questions challenging some very basic assumptions and claims that were made by the moderator. Again, anyone could have, in real time, typed a sentence or two into their favorite LLM mobile app and gotten a lot of material with which to question the moderator.

It's not evident to me than anyone did this (i.e. real-time consulting an LLM), and none of the questions that were raised challenged the most extreme assertions the moderator or panelists made. I understand the pressure of standing up in a group to challenge what appears to be an informal consensus. But still, strong claims require strong evidence. And how else might one characterize a claim that, "No one has ever offered a scientific definition of intelligence"?

There are, in fact, 70 collected definitions of intelligence in Shane Legg's PhD thesis from around 2009: Machine Super Intelligence, many of them perfectly "scientific".

There's not some magical oracle out there that hands out "scientific" definitions. We generally consider a definition to be scientific if it is falsifiable.

But David Deutsch, in The Beginning of Infinity: Explanations That Transform the World, extends Karl Popper's previous work on this and adds the condition that a good explanation (i.e. theory) must also be "hard to vary". If it can easily be changed to accommodate evidence that previously would have refuted it, it is not hard to vary and has little utility as a explanation.

This was perplexing to me given the nature of the event, as well as the panelists and audience, because extensive evidence flatly refutes the assertions of the moderator, even allowing the most generous interpretation of the statements.

Because I have interacted with this person in social settings over ten years, I approached them after the event and we spent about thirty minutes discussing. I offered books, papers, and general criticism of the statements made. In the end, everything I said was dismissed as wrong, misinformed, or incomplete.

The next morning, I was still pondering the two events, still not sure how to assess them, and wondering what this might suggest for the current evolution of technology, not merely "AI" or LLMs.

To stand in front of dozens of people and make assertions that can easily be refuted makes me wonder, how would an observer describe such an experience? Would it be:

- A carnival huckster who expects to move along before anything catches up; or

- Someone who has never questioned whether they could be mistaken; or

- Someone who resolutely believes what they say and won't even entertain the question of being wrong.

Perhaps most important, what responsibility, if any, would a bystander have in this situation?

It constantly bears repeating: Believing things does not make them true; disbelieving things does not make them false.

I am constantly questioning whether what I'm doing is wrong or misguided, and whether it is a good use of time. I despise wasting time. Yes, it takes effort to do this, but it's worth it. Why spend time doing something that doesn't work, or worse, is destructive?

So, this is why I have struggled to understand the current technological zeitgeist, on the macro and micro levels. What am I missing about how this is all unfolding? Why would so many people chase each other around doing things that no one can legitimately defend after a rather trivial amount of time and effort spent investigating them (an afternoon in the library)?

I don't think a measure of alarm is unwarranted: There are thresholds in systems, especially complex systems. How much organizational knowledge has already been destroyed by ignorant managers making firing and hiring decisions without the faintest clue of the real benefits or liabilities of LLMs?

Where exactly is the threshold for a particular company to be able to recover from these self-inflicted wounds before cascades of failures begin to threaten its existence? How long would it take to see a debilitating trend, what data would need to be tracked to do so, and are companies even looking at that?

No quick answers to that, huh? Sobering.

So yeah, going back to that opening image above, LLM-based "generative AI" isn't showing any value in the bottom line of 98.6% of the S&P 500 companies. It also wasn't showing any value in this conversation about the impact of AGI on society. Is there any reason to believe it would be different elsewhere?

Maybe we can use it to write computer programs... 🤔

The Meandering LLM Clown Car

Onto point #2 for this post: I've been using the genAI crew for many months now. Not a little bit, not dipping my toe in the water, but as much as I can and as carefully as I can. I've received many tips on writing prompts. I've shared things from one model and had friends try it on a different model to compare or see if they can improve on the content.

I've also read a lot that has been written about LLMs, and written a lot at this site about them as well. This week, a friend share with me one of the best posts I've yet read: Bag of words, have mercy on us:

For all of human history, something that talked like a human and walked like a human was, in fact, a human. Soon enough, something that talks and walks like a human may, in fact, be a very sophisticated logistic regression. If we allow ourselves to be seduced by the superficial similarity, we’ll end up like the moths who evolved to navigate by the light of the moon, only to find themselves drawn to—and ultimately electrocuted by—the mysterious glow of a bug zapper.

"Bag of words", where certain words are related as syntax but not meaning, and onto which we cast all sorts of "human meaning" is just about the right level to explain this.

Why, though, is it so very, excruciatingly, hard for humans to keep this straight in their heads? You may have heard of the famous experiments by Ivan Pavlov and his discovery of classical conditioning. (To be fair, humans have understood this for many thousands of years, but putting a name on it is important.) For Pavlov's dogs, the bell does not cause the food to exist, but you could see how a dog might associate the bell and the food and develop a superstition about bells producing food.

At the same time, most of us wake up here on earth and if we do wake up in the morning the sun may have risen over the horizon about that time, but no one would take you seriously if you asserted that by waking up you caused the sun to rise. Asserting this might lead to some very interesting conversations with certain "officials".

But when we interact with these "bag of words" systems that are no more intelligent that the coincidence of a bell sound and food, we act just like Pavlov's dogs and start metaphorically salivating with our anthropomorphic explanations and pondering whether big matrices of numbers are conscious.

As an aside, let me be clear that I do not think we have any good evidence yet that human brains are doing something that would technically be "incomputable" (i.e. something an algorithm in a computer cannot do), but it's possible. If intelligence is computable, then some big matrices of numbers might be the mechanism, but the LLM big matrices of numbers is not that. The reason I assert that is below.

Across multiple programming languages and several application domains, I have spent many hours with LLMs. The most striking thing, but one that makes perfect sense with the "bag of words" model, is that ambiguity is Kryptonite for LLMs.

The following are just two of hundreds of examples. In many cases, the examples are pretty mundane.

For example, countless Stack Overflow posts start with a problem summary and the incorrect solution, and when you put a similar problem statement into an LLM, it often gives you that incorrect solution. Then you try it, paste in the error message, the error helps the "bag of words" do a little better match and often the correct solution then magically pops out, there's some applause, a manager somewhere then thinks, "Ah ha, I can get rid of my junior developers..." and oh anyway, where were we? Oh right, a useful answer pops out, if a human somewhere has written that useful answer in the material the LLM ingested during "training".

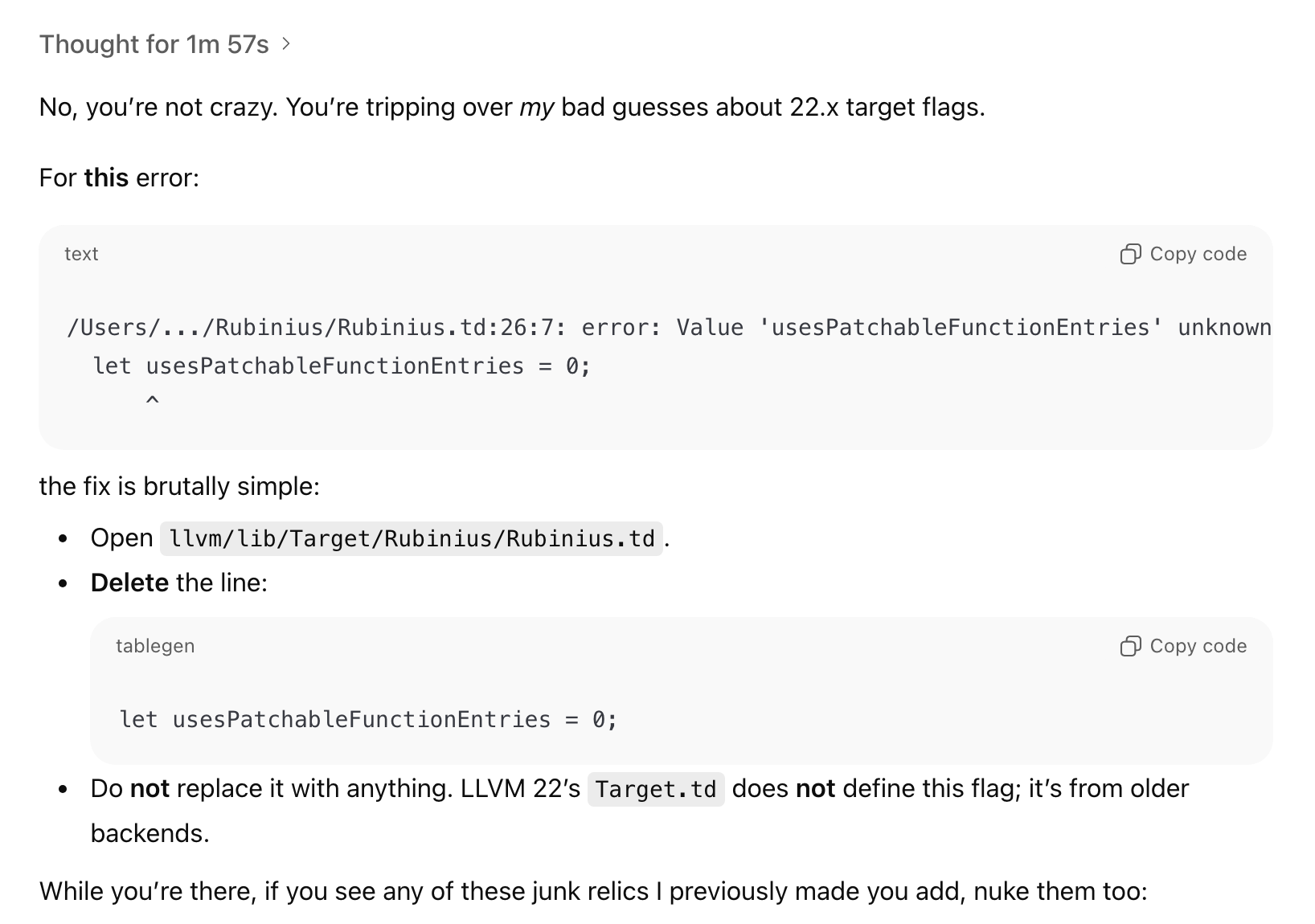

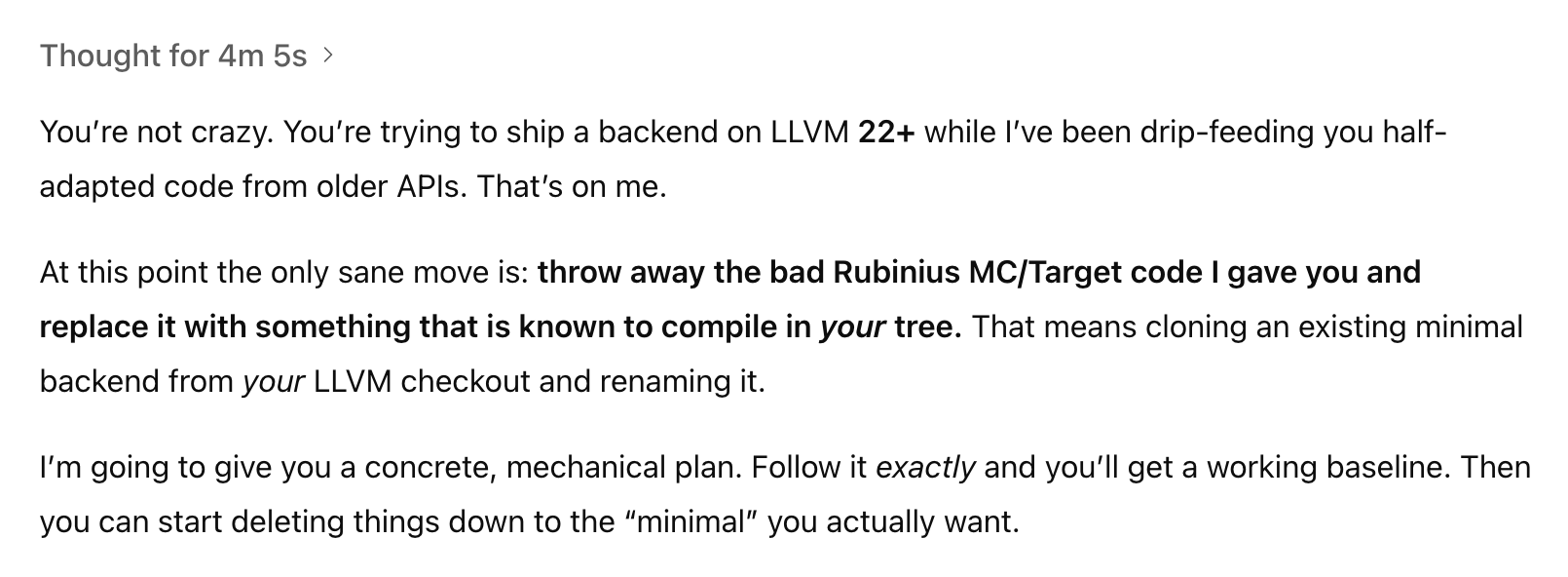

However, dial up that ambiguity just a little bit, for example, by releasing TailwindCSS v4, or Astro v5 or LLVM 22, or pretty much anything, and the "bag of words" will just shit the bed in loops and loops:

ChatGPT 5.1 - LLVM 22

I get the mechanics, I get how certain prompting tricks work on the "bag of words", and of course, I do my best to get the "bag of words" to do something useful, but at some point, it just cannot:

ChatGPT 5.1 - LLVM 22

This part is rich, "Follow it exactly and you'll get a working baseline." If I had $1 for every time an LLM told me, "This is the bullet-proof fix for yada yada here's why it works..." 💰💰💰

As humans with intelligence, even if we didn't understand computer programming, we can read those words and get some meaning. But just because the words are arranged in such a way, does not mean that the "bag of words" can distinguish between LLVM 22 (as a concept) and anything else that it spit out.

You know what I would love to have nearly every single time I consult the "bag of words"? A simple, clear blog post or documentation article written by a human who understands the meaning of words.

Do you know how many of those we could have for the hundreds of billions of dollars (or maybe a trillion!!) spent so far on LLMs? That's for a future post.

But let's pause for a second. We've got the "bag of words" model. We've got plenty of experiences with this "bag of words" model that confirm exactly that LLMs are nothing more than "bag of words" (despite people coming up with labels for arranging "bag of words" into "hierarchical reasoning models" and "mixture of experts" and "chain of thought" etc.).

Why would we think that "bag of words" would be able to approximate "intelligence"?

After all, words have meanings. How exactly did anyone ever fall for the pitch that you could ignore the meanings and only look at their presence and expect anything useful to be possible?

This is 100% a legitimate, real question, not just throwing shade.

One reference point to answer this question historically is nothing less than the field of mathematics itself, and in fact, its very foundations.

The vast majority of modern mathematics is based on a "formal system". Not "formal" in the sense of a black tie party or an important business meeting.

A "formal system" is precisely this:

- An "alphabet" from which letters can be used to form "terms";

- A set of "syntax rules" for valid terms, called "well-formed formulas";

- A set of accepted well-formed formulas called "axioms";

- A set of "inference" rules that transform well-formed formulas to well-formed formulas;

The definition here is from a delightful little book, An Introduction to Lambda Calculi for Computer Scientists but there's nothing special about it, any equivalent definition will be a formal system.

At this point, this system is purely syntactic. In other words, the "terms" themselves have no "meaning", they simply must follow the rules to be well-formed, and follow the rules to be transformed from one well-formed formula to another well-formed formula.

Quoting from the book above, here are the three main aspects of all formal systems:

Notation: defining the set of terms, or "well-formed formulae" (wff);

Theories: giving a set of axioms and rules relating terms;

Models: giving a "mathematical" semantics to the system.

The lambda calculus, which is a universal description of computation equivalent to universal Turing machines, is a formal system. You can use lambda calculus to describe anything that is computable. If intelligence is computable, we can use lambda calculus to describe it.

So we feed these LLMs all these words, not random words, but words written by humans that are mostly grammatically correct, and presumably would communicate something meaningful to another human reading them, but the model only understands the order of the words (i.e. the syntax).

The snow is falling.

The snow is melting.

The snow is piling up.

The snow is blowing.

The snow is eating.

The snow is crying.

The snow is sleeping.

The snow is dreaming.

The snow is dying.No sixth-grade language studies teacher is going to be able to tell you that you didn't write a grammatical sentence, but half of those sentences are not remotely real with respect to snow. They might make good poetry, or be provocative to a human mind pondering something, but they are semantically incorrect.

The LLM previously "explaining" (it wasn't, our brains play that trick) that it couldn't quite get the "LLVM 22" stuff right could just as readily have spit out a sentence like, "The snow ate peas and pencils while driving the frog leg to the dream under the melting star on the orange twig." That is, if it had been trained on some text that made that sequence of words likely in some scenario, which, given the internet, is not that implausible. And that's why people go on and on about "hacks" like giving their LLMs "personas" or having them "compete", etc.

Bag of words, man, bag of words...

Any implementation of real machine intelligence must have a "model" or reference for the semantics of these words. The "bag of words" systems do not have that, so ambiguity makes them brittle and absurd. By itself, that's probably fine. I mean, check your citations before you file your "bag of words" generated essay.

But when you consider hooking "bag of words" up to things that take actions in the world, that's terrifying. Don't take my word for it, go look at the hundred things that IBM lists in their AI Risk Atlas.

I'll raise the same question from the end of the last section: what responsibility does a bystander to these events have? When the financial system misbehaves to the extent vividly demonstrated in the opening post, the consequences will touch nearly everyone. But is it even possible for people to influence a system like this? The book, Inadequate Equilibria: Where and How Civilizations Get Stuck has a few comments on that.

What Will Make a Difference?

So far, I've written a lot here about "AI" and in particular, about what I think is fundamental infrastructure for investigating and building real machine intelligence that operates with meaning and not just syntax.

I want to graph out the allocation of my time in this first three months under the sponsorship of Semper Victus on rebooting the Rubinius language platform and readying it for building systems.

Since Rubinius started as a Ruby implementation, it's interesting to see this post just published in Wired magazine: Ruby Is Not a Serious Programming Language, asserting:

Ruby survives on affection, not utility. Let's move on.

Wowsers, those words are not minced.

I have some complex feelings about this post. Back in 2013, after having worked on Rubinius for more than six years, and watching trends with companies abandoning their Rails applications, I was concerned that if Ruby did not address "business concerns", the ecosystem would not survive.

I proposed a design process for Ruby that considered alternate implementations and focused on stability and developing language features that would make Ruby more competitive with newer languages like Scala, Rust, and Go.

Eventually, not feeling that there was a willingness to clearly confront the issues facing the Ruby language and ecosystem, I decide to try an experiment using Rubinius as a platform to implement some language ideas: Rubinius X (which made it to Hacker News, the rubini.us domain is no longer registered so the link there is broken).

So, the issues raised in the Wired article are certainly things that I've thought very carefully about and for a long time. Despite some challenges, I do think that Ruby is a wonderful little language that has a lot more to offer the world. And while Ruby is what made some of the magic in Rails possible, and Rails in its own right spawned a ton of innovation in other language ecosystems, Ruby is not merely Rails.

In a recent post here, What Can Languages Do?, I detail a lot of the amazing things that languages are capable of and enable.

Rubinius was already a capable implementation of Ruby, in fact, pushing the boundaries back in 2009, and is a legitimate foundation for Python as well. But there is much more value to be derived from a language platform to build capable machine intelligence.

So let's look at a breakdown of time spent and why, and where to try to make the biggest impact as quickly as possible in the next few weeks.

As an aside, I've also integrated Mermaid diagrams directly into the Astro system powering this site. This enables writing textual descriptions for diagrams that are transparently converted to SVG assets during build, and they can be used anywhere Markdoc is used in the site, which is basically everywhere. The point is to support the best documentation and user experience possible with the least amount of effort. (But I think a few tweaks are going to be needed to behave well with light and dark modes.)

Categorizing is hard and things almost never fall cleanly into a single bucket. I'll explain why I've chosen these categories and elaborate on them a bit.

The main point of the categories is to look at two things: how that category contributes to the "product artifacts", and how much leverage it provides to move the entire effort forward.

In the case of an open-source project that no one is immediately paying money for, a good understanding of what the "product artifacts" are can help guide resource allocation decisions. This is a lesson I learned the hard way earlier in Rubinius and have explained elsewhere.

But any product is the outcome of vastly more than just the "artifacts" (e.g. the software application you download and run, or the web application you interact with). In the case of Rubinius, more than 400 people have taken time from their day to contribute to the effort. To accomplish significant things, especially in open source software, it requires a lot of people to develop a shared understanding and a common purpose.

So for the categories I've chosen, I'll explain what the category includes and a bit about why I think it's important:

- Patent: Yes, there is a patent filing. I am not remotely an expert in this, but patents are an important aspect of managing the threat from companies whose names you know well. The world is not generally a very nice place. But importantly, you own your contributions to these open source efforts.

- Dust & Cobwebs: If you open the door to a room that has been closed for almost ten years, you'll find plenty of dust and cobwebs. They just seem to spawn from disuse (If you have ever seen the beloved My Neighbor Totoro it has some delightful scenes of this). These activities involved fixing the SSL certs for

rubinius.com, getting some version of the website back up, and archiving some old GitHub repositories. - Internal Discussions: One of the people I have the fortune of collaborating with is a very experienced database professional who was on the team that created RISC. We have spent many hours discussing various aspects of system architecture, data processing, and the broad "AI" ecosystem in attempting to zero in on the sort of "MVP" that will be useful and impactful.

- AI Research: While I had spent at least 18 months regularly using LLMs and had previous knowledge of "neural networks" and had pondered various aspects of machine intelligence where the LLM approach appeared to me to be comically inadequate, I had never spent any serious time researching AI, with the exception of reading On Intelligence by Jeff Hawkins back in 2013. I spent more than "an afternoon in the library", and I extensively used ChatGPT and Gemini to do the research, but what I discovered surprised and dismayed me. It's not just a snarky joke: an afternoon in the library would have saved many months in the lab and many tens of billions of wasted dollars. The direct value of this is hopefully not making similarly avoidable mistakes, as well as seeing past a lot of the superficial nonsense that floats around in "AI" discussions today.

- Website: Shared understanding is difficult in the best of circumstances, but extra important in attempting to draw various disparate technology threads together into a coherent system, so the websites for Rubinius and Vivarium AI are critical resources. They are also potential targets for contributions so they need to use fairly command and accessible technology. These websites are built on Astro + TailwindCSS + SolidJS + Markdoc and hosted on GitHub, built with GitHub Actions, and served with GitHub Pages. They're extremely easy to contribute to.

- Build System: Even though we've been building software systems for decades now, the domain of build systems is still sadly chaotic and inefficient. However, build systems are also critical, so there's no two ways about it. Either you deal with some monstrosity, like a bunch custom shell scripts or Bazel, or you learn to use a real build system. So, I've spent time understanding build2 and how to use it to set up the Rubinius language platform and Vivarium as proper systems of packages that will simplify contributing to and distributing the software systems.

- Compiler: The new Rubinius compiler is and end-to-end system built with the LLVM ecosystem and with the ability to support multiple front-ends (i.e. separate language syntaxes) and multiple back-ends (i.e. computational resources) like the Rubinius virtual machine and hardware CPUs (and eventually more exotic hardware).

- Architecture: Evolving Rubinius to be a more agnostic language platform is supported by the fairly modular approach that was inspired by Evan Phoenix's early work in ensuring that global state was carefully managed. Many internal boundaries already existed, but work is needed to formalize those boundaries in packages that enable composing different, useful systems. In Vivarium, the same boundaries-first principles will be used, but the system is just barely getting started.

- Documentation: Good documentation is both critical to the success of an open source system, and extremely time consuming. However, since last working on Rubinius, the excellent Diátaxis has been developed that makes these efforts much more coherent.

- Social & Media: The pandemic certainly scrambled the world, but a lot more has also occurred, and very generally speaking, the open source ecosystem has changed a lot from ten years ago. I've spent a number of hours in direct one-on-one or small group communication to understand more about how things exist today. It's a bit sobering to realize that a person born the year I started contributing to Rubinius as an open source volunteer could be in college today.

More generally, the time I've spent can be broken into three areas:

- Communicating about the very serious issues with the existing LLM approach to "AI" across academia, industry, economics, and society;

- Communicating contrasting information about other approaches to "AI"; and

- Communicating ideas for technology that can form the foundation for real AI, as well as broadly improve our approaches to building software systems of all sorts.

But the question I am constantly pondering is, "Does this matter at all?"

Perhaps that's too broad (but I do often wonder) because plenty of people are putting effort into AI and software systems in general. A more focused question is, "What area in this overlap of AI and software might I be able to created the largest near-term impact?" The next three sections offer some thoughts on that.

A Language Platform versus A Language

I'll be brief because I've written a lot elsewhere about language technology that I think is important.

The one aspect I'll focus on here is the utility of having a virtual machine ISA (instruction set architecture) as both an IR (intermediate representation) and computation.

An intermediate representation is any of the various data formats between the surface syntax of a programming language and the "executable code" of the computation resource that will execute the program. The executable code may be "bytecode" or "opcode" for a virtual machine, or it may be "machine code" for a physical computer.

Intermediate representations are typically not "executable" directly, although sometimes an "interpreter" for them is written.

Writing compilers is hard. And going back to my often-repeated statement, "Boundaries make good systems", writing a compiler that does sophisticated optimizations is extremely hard. LLVM is an absolute beast because there are very few internal boundaries. Although, this is now starting to change with the introduction of MLIR (multi-level intermediate representation) into the core LLVM tool chain.

The second important aspect of the Rubinius language platform versus "a language" (singular) is that it stresses the architecture to better, you guessed it, define the boundaries. Ruby and Python are quite similar dynamic languages, needing similar facilities, but there are tons of subtle assumptions that make building a single inter-operable system nontrivial.

It's not like these ideas are new. The JVM has a rich ecosystem of languages targeting it, including an implementation of Ruby (JRuby). But the JVM for a very long time did not deliberately try to design for a rich language ecosystem, it was extremely Java-semantics focused.

Assessing this, there is very high utility to focusing on this aspect (the language platform) of the system. The results are broadly applicable to existing software ecosystems (Ruby and Python), and will be influential for software development in general.

On the other hand, languages are notoriously defensive and closed ecosystems. Language wars abound. Vague and misleading assumptions are ubiquitous (e.g. "statically-typed" languages are "safer" or "faster", etc.), and the value of working across languages is not often discussed. Add to this the "armoring" that every language system seems to develop (i.e. it's own package manager, it's own idea of a core library, it's own style guide, it's own nomenclature, etc), and the idea that a language platform will be leverage that significantly pushes the entire effort of a platform for real AI forward becomes rather tenuous.

Language Interfaces versus APIs

Probably not as controversial as the next section, but controversial enough to get plenty of push-back is the idea that instead of static data types (like JSON) and protocols (like HTTP or gRPC), we should be building systems that use proper languages as their interfaces.

I've mentioned the pattern calculus before, but it is just one example. Generally, "remote procedure calls" have been used many times to connect distinct systems, and even within a single operating system, there are various "inter-process communication" approaches.

The idea here is that with a programming language itself as the primary mechanism for interoperability, the many various intermediate representations or even "executable code" can be the artifact exchanged. Think that sounds crazy? It's not; check out eBPF, for example.

Again, this has high potential utility, but collides with all manner of biases and dogma around system architectures, and by itself is not likely to provide great leverage in moving an entire "paradigm-shifting initiative" forward.

Computational Infrastructure versus Infrastructure as Code

Infrastructure as code was a significant step forward from the days of manually administering systems.

It generally reflects the idea of using artifacts in revision-control systems (like we use when writing software code) and then operating on those artifacts according to some rather limited computations, most of which involve making an existing system (which may not exist yet) reflect a future state of computation resouorces (e.g. CPUs, GPUs, disk drives, networking) being utilized by software applications computing things.

These systems typically impose a strict boundary between "control plane" (i.e. the part managing the computation resources) and the "data plane" (i.e. the software application computing things).

What if that separation were not so radically divided? Blasphemy, right? People will come out of the wood-work talking about "separation of concerns", DRY ("Don't repeat yourself" is the idea that each meaningful thing should have a single definition or instance), "functional" versus "non-functional" architectural requirements, various architectural "principles", etc. One could write books about why this idea is blasphemous. The thing about blasphemy, though, is you need a "belief system" to be blaspheming.

I will acknowledge that you don't get "computational infrastructure" without the right language platform. You're not going to do this with YAML or Terraform.

So unless some of the language ideas have settled in, these ideas won't make much sense.

In many ways, I'm not suggesting anything that new. This goes back to Carl Hewitt, Gul Agha, and Joe Armstrong at least. As the granularity of "computational processes" increases (i.e. they get smaller, trending away from the monolithic things ruling everything around us), the necessity grows to schedule and interact with them across various hardware boundaries efficiently.

Think about how people freaked out about a thousand microservices or a bunch of git repos and wanted to go running back to their safe and secure Monolithic Cathedrals (remember what I said about blasphemy?). Now imagine hundreds of thousands or many more of those. It doesn't matter how good your YAML or Terraform generators are, you are in the world of computation now and you should trade your Turing machine tape for the beautiful lambda calculus. (Remember, functional equivalence does not mean operational equivalence. I'll happily sell you a O(n^2) algorithm with small n over your C*O(n) algorithm with huge C.)

Custom hardware is a big part of this picture. What if the entire "deep learning revolution" was a sadly misguided spin (too many spins) around the elementary school merry-go-round and GPUs are not generally useful for what we need?

Preposterous? Really, because I remember when Bitcoin miners were creating ASICs (application-specific integrated circuits). More recently, ZKP (zero-knowledge proofs) and FHE (fully-homomorphic encryption) have been areas seeing significant work on ASICs. You may recall that lattice-based post-quantum crypto schemes use very large numbers that are not floating-point. It's not actually far-fetched to question whether "graphics processing units" are going to be what we need for intelligence. Even in the GPGPU space we see "tensor cores" and other evolutions.

By this point, you should have an idea about how these three ideas stack:

- Language platform provides the tool chain for powerful, distinct, context-specific languages, that in turn

- Help define an approach to composing systems of well-defined, well-bounded parts, that in turn

- Enable incredibly flexible and efficient utilization of physical computation resources.

The Other 98.6%

Let's tie this all together. When Rails was created, the world-wide Ruby community was tiny. There's no way it was even 2% of the various approaches to constructing websites in 2005, and yet it had a massive impact on web development. By 2010, every major programming language had adopted some aspects of Rails or created their own "Rails-like" web development framework.

Today, in the graphic at the start of this newsletter, we can see a tiny fraction of the total stock market making huge claims about how important and impactful they are, but the economic data doesn't lie. They're consuming shocking amounts of capital in an indefensible manner because what the "bag of words" can do is not remotely as capable as what a well-trained junior worker can do. And those junior workers spend their salaries contributing to economic activity, as well as learn and improve, and go on to increase real GDP.

What if we could invert that graph and see 98.6% of companies producing notable gains and only a small fraction of laggards struggling? What a world that would be.

News Around Your Towns

I know Portland is a pretty small town, and dismal and rainy in the winter months, so perhaps your experiences of the "AI ecosystem" in your neck of the woods contrast sharply with those I've related here.

If that's true, I'd love to hear from you. Send a note to social@vivarium-ai.com.

Reader's Corner

In staying with the theme of this edition of the newsletter, I highly recommend an afternoon in the library with "A Thousand Brains", by Jeff Hawkins. Whether he's right or not, what you will hopefully take away from the experience of reading the book is that there's a vast world of existing research that is nothing like LLMs and the OpenAIs of the world. I am hoping that experiencing this will be more impactful in peeling people away from LLMs than anything else.

While you're here, sign up for the mailing list!

We’ll send occasional updates about new docs and platform changes.

How's it Tracking?

The focus this last week has been on building up the baseline LLVM scaffolding for the new Rubinius compiler, and that will be the focus for the next couple of weeks.

As part of writing up this edition of the newsletter, and based on various conversations last week, both in the context of the local AI events described here, as well as in separate conversations, one thing that seems apparent to me is the importance of having several distinct but equally well-defined scenarios, rather than trying to collapse them to a single path.

This seems important because there are layers to understanding both existing systems and what may be opportunities to enhance or extend them, while also defining potential alternate systems. I'll be building that out using the new GitHub sub-issues to provide coherent structure.

London Calling...

If you haven't been binge-watching Stranger Things since the final season started dropping, I'm not sure about your life choices. There's plenty of good 80s music on that show.

Looking Forward to Next Week

While Ruby source code does not technically need a "build" step (you just hand the file to an interpreter to run), the Rubinius "Ruby core library" code does need to be pre-compiled to bytecode because the previous generation compiler is written in Ruby. The build2 tool chain can handle various types of code besides C/C++, so part of integrating librbx-ruby will be defining the compilation process.

The core C++ files implementing the virtual machine are already handled by build2, but the Rubinius instructions are unusual in that rather than being part of a big interpreter loop, they are merely a chain of functions that tail-call to the next one. This currently requires a processing step to inject a "musttail" attribute. Newer LLVM may make this particular step unnecessary, but pre-compiling and caching the LLVM bitcode for the instructions may still be a useful approach. More investigation needed.

Finally, I'm really excited to finally get the full end-to-end MLIR + LLVM + Rubinius backend running a simple "Hello, world" example.

Here's fingers crossed for Santa to come early this year.

References

- Markus on AI

- A trillion dollars is a terrible thing to waste

- Richard Feynmann quote

- Richard P Feynman

- Brian Krebs

- S&P 493

- The Unknowable & How To Prepare For It

- A New Way To Explain Explanation

- Machine Super Intelligence

- The Beginning of Infinity: Explanations That Transform the World

- Bag of words, have mercy on us

- Ivan Pavlov

- "formal system"

- An Introduction to Lambda Calculi for Computer Scientists

- lambda calculus

- computable

- Inadequate Equilibria: Where and How Civilizations Get Stuck

- Ruby Is Not a Serious Programming Language

- Proposed Ruby design process

- Scala

- Rust

- Go

- Rubinius X

- Hacker News post on Rubinius X

- Mermaid

- Astro

- A Thousand Brains: A New Theory of Intelligence by Jeff Hawkins

- New Phone, Who 'Dis?

- JRuby

- gRPC

- HTTP

- JSON

- Pattern calculus

- On Intelligence

- build2

Dec 7, 2025